Trade and Chinese Relations with Foreigners

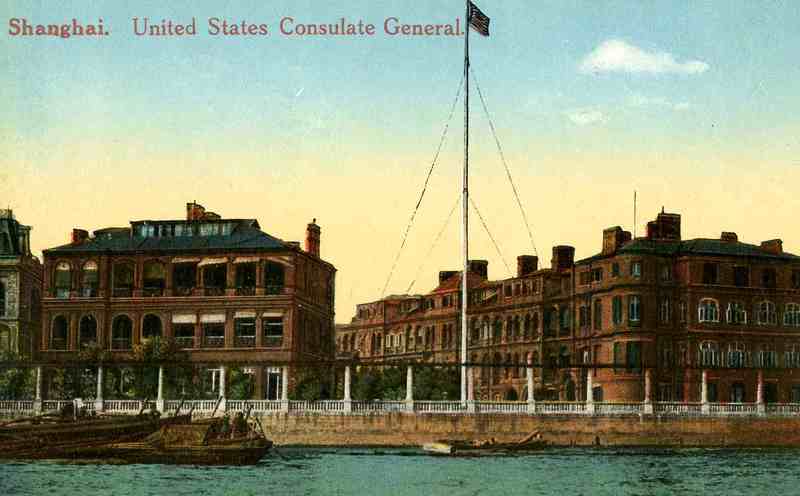

By the Chinese ports, there would be numerous American and European posts. This is a postcard of the United States Consulate General at the time and next to it there were other foreign buildings. This postcard catches the readers attention because it doesn't seem like a Chinese neighborhood. As Whitman noticed, "the only thing to suggest China [was] the ever-present Chinese coolie and the signs in Chinese characters. Except for these two things we might have thought it an American or European port." A little farther, there was a British park in which Chinese people were not allowed to walk in. This suggests foreigners and Chinese citizens would not interact much with each other.

FOREIGN HONGS

Ever since the first trade relationships with China, foreigners were required to live in a separate quarter of the city. Foreigners “hongs” or merchant shops were situated between the city wall and the river so foreigners did not have much interaction with the city citizens. Therefore, the Americans that went to China saw a very small part of the empire. In the 18th and early 19th-centuries the trade was restricted to Canton, in a very rough, walled-off part of the city; where the Americans "were exposed to some of the meanest elements of Chinese society. They felt they were being cheated, they didn’t like what the Chinese ate, they made fun of how they walked, how they looked, how they dressed. There were a number of things that American merchants found less than commendable about the Chinese”.[1]

There was always an appointed official who was in charge of collecting duties from foreign trade. Just like the Ma Fu (horse driver) was entitled to a “commission” from the shop-keeper on everything that Whitman and his friends purchased, during maritime trading, the Hoppo (official superintendent of maritime customs) was in change or collecting duties on foreign trade and sending them to the Imperial household.

In conclusion, foreigners would never really interact with Chinese people as they would normally stay and conduct their business in their chambers. Therefore as Whitman wrote in his journal, "not much of the real Chinese life is seen in the foreign concessions of Shanghai. Only if they make a trip into the native city they would see Chinese in their native element."

[1] Goldstein, Jonathan. "Philadelphia's Old China Trade and early American images of China." Pennsylvania Legacies 12, no. 1 (2012): 6+. General OneFile (accessed December 13, 2017). http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A394348489/ITOF?u=mlin_n_state&sid=ITOF&xid=10e3312f.

FLOWERY-FLAG DEVILS

The Chinese weren’t sure of what to make of Americans. They called them the “New People” at first, but later they would call them the “Flowery-Flag Devils” [1] because of the stars on the American Flag which looked like flowers to them. The Chinese believed that all other countries were beneath them at some level and had inferior cultures. In general, the Chinese held a condescending view of foreigners.

During their visit to the Chinese market, Whitman and his friend decided to visit several silk stores and they were expecting to see the different silk fabrics in display, however, they noticed that they were shown only the products which they asked to see. Whitman wrote in his journal that he received the same treatment in many other stores: they were greeted and “served tea with much grace, but goods were shown with apparent reluctance”. They also visited silver and jewelry stores and a watch and clock store where they were courteously received, however whenever there were Chinese people present, they were given first attention while the foreigners were waited on last.

This interesting observation speaks about the Chinese-foreign relations at the time. Although in many occasions, Whitman and his friend were treated cordially, they were repeatedly reminded that they were foreigners and were not as welcome or treated the same as Chinese people. This could be due to past relationships with foreigners that caused Chinese people to distrust them and also because “The foreigner is still enough a novelty to the people in that part of the city so that he quickly draws a crowd. As we entered a shop, the shop-keeper would stand guard at the door until we were ready to go” [2]

[1] Landrigan, Leslie. "The Boatload of Ginseng That Launched the China Trade." New England Historical Society. February 22, 2014. Accessed December 18, 2017. http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/boatload-ginseng-launched-china-trade/.

[2] Walter G. Whitman, Manuscript draft of Observations of Life in China, ca. 1926., Walter G. Whitman Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.